Introduction

When patients undergo surgery, the operating room is kept cool so that the physicians in heavy gowns will not be overheated. The price for the surgeons’ comfort could be paid by the patient. The exposure to cold, in addition to impairment of temperature regulation caused by anesthesia and altered distribution of body heat, may result in mild perioperative![]() Perioperative:Around the time of surgery. hypothermia

Perioperative:Around the time of surgery. hypothermia![]() Hypothermia:Abnormally low body temperature. (approximately 2°C below the normal core body temperature). As a result of the hypothermia, patients may have an increased susceptibility to perioperative wound infections or even morbid

Hypothermia:Abnormally low body temperature. (approximately 2°C below the normal core body temperature). As a result of the hypothermia, patients may have an increased susceptibility to perioperative wound infections or even morbid![]() Morbid:Pertaining to, arising from, or affected by the disease. cardiac events.

Morbid:Pertaining to, arising from, or affected by the disease. cardiac events.

In Austria, Kurz, Sessler, and Lenhardt (1996) investigated whether maintaining a patient’s body temperature close to normal by heating the patient during surgery decreases wound infection rates. In a separate study at Johns Hopkins, Frank, et al. (1997) examined whether maintaining a patient's body temperature close to normal during surgery is associated with fewer incidents of (morbid) heart attack.

Synopsis

Abstract

Two independent studies, one in Austria and one at Johns Hopkins, showed that maintaining a patient’s body temperature close to normal by heating the patient during surgery decreases wound infection rates.

Extensions

Tabulated results

6 Questions

Experimental Design, Randomization, Double Blinding, Confounding Factors, Confidence Intervals for Difference of Means

Basic: Q1-6

Protocol

Austrian study

All patients included in the study were undergoing colon or rectal surgeries, which are typically associated with a high risk of infection. The night before surgery, all patients were prepared for the next day’s surgery in a standard manner. Both during and after surgery patients were given liquids intravenously in hopes that this would decrease the chance of infection caused by bacteria from the wound entering the bloodstream. Random assignment of patients to the temperature management groups was done during the induction of anesthesia. Codes which had been generated by computer and numbered and sealed in opaque envelopes were used for the random assignments. The two groups were the normothermic![]() Normothermic:Near normal temperature where normal body temperature is around 37.0 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). group (patients’ core temperatures were maintained at near normal 36.5°C) and the hypothermic group (patients’ core temperatures were allowed to decrease to about 34.5°C). While intravenous fluids were administered through a fluid warmer machine for both groups, only the normothermic group had the warmers activated. Additionally, a forced-air cover was used on the upper bodies of patients in both groups, but it delivered heated air in the normothermic group only (it delivered surrounding air in the hypothermic group). In order to keep the surgeons and operating room personnel from detecting which patient was in which group, shields and drapes were placed over all devices which would indicate group assignment. Postoperatively there was no controlling of patient temperatures, and the patients did not know their group assignments. All patients were able to self-administer pain killers.

Normothermic:Near normal temperature where normal body temperature is around 37.0 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). group (patients’ core temperatures were maintained at near normal 36.5°C) and the hypothermic group (patients’ core temperatures were allowed to decrease to about 34.5°C). While intravenous fluids were administered through a fluid warmer machine for both groups, only the normothermic group had the warmers activated. Additionally, a forced-air cover was used on the upper bodies of patients in both groups, but it delivered heated air in the normothermic group only (it delivered surrounding air in the hypothermic group). In order to keep the surgeons and operating room personnel from detecting which patient was in which group, shields and drapes were placed over all devices which would indicate group assignment. Postoperatively there was no controlling of patient temperatures, and the patients did not know their group assignments. All patients were able to self-administer pain killers.

Determinations of when to begin postoperative feeding, suture removal, and hospital discharge were made by attending surgeons who were unaware of the patients’ group assignments and core temperatures during surgery. Routine surgical considerations were involved in the discharge decisions. Note that the study was done in Austria, a country with managed health care, so that there are no insurance or administrative issues that might contribute to patient-to-patient variation in the length of stay at the hospital.

Johns Hopkins study

The subjects in the study were 300 patients undergoing abdominal, thoracic![]() Thoracic:The chest cavity area containing the heart and lungs, etc., or vascular

Thoracic:The chest cavity area containing the heart and lungs, etc., or vascular![]() Vascular:Blood vessels. surgery, who either had documented coronary

Vascular:Blood vessels. surgery, who either had documented coronary![]() Coronary:Arteries which supply the heart tissues. artery disease or were at high risk for coronary disease. These patients were randomly assigned to receive routine thermal care (hypothermic care) or normothermic care. According to Frank, et al. (1997),

Coronary:Arteries which supply the heart tissues. artery disease or were at high risk for coronary disease. These patients were randomly assigned to receive routine thermal care (hypothermic care) or normothermic care. According to Frank, et al. (1997),

… routine thermal care … was delivered according to the following protocol. The thermostat in the operating room was set to approximately 21°C. Intravenous fluids and blood were warmed [with the same type of device]. A [specific] heat-moisture exchanger … was used in the respiratory circuit for patients receiving general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, the patient was covered above and below the field [i.e., location of surgery] with one layer of paper surgical drapes. Postoperatively, either one or two warmed cotton blankets were placed over the patient, at the nurse's discretion.

Patients in the normothermic group were treated as follows. … The thermostat in the operating room was set to approximately 21°C, fluids and blood were warmed, and a heat-moisture exchanger was used in the respiratory circuit. Depending on the surgical site, an upper- or lower-body forced-air warming cover was placed over the patient. During the intraoperative and postoperative periods, both the temperature and airflow settings were adjusted to maintain core temperature at or near 37°C.

Since temperature was monitored via probes on the arm and fingertips during the postoperative period, the forced-air blanket was placed over the patient's legs and trunk, leaving the monitored arm exposed.

Results

Austrian Study

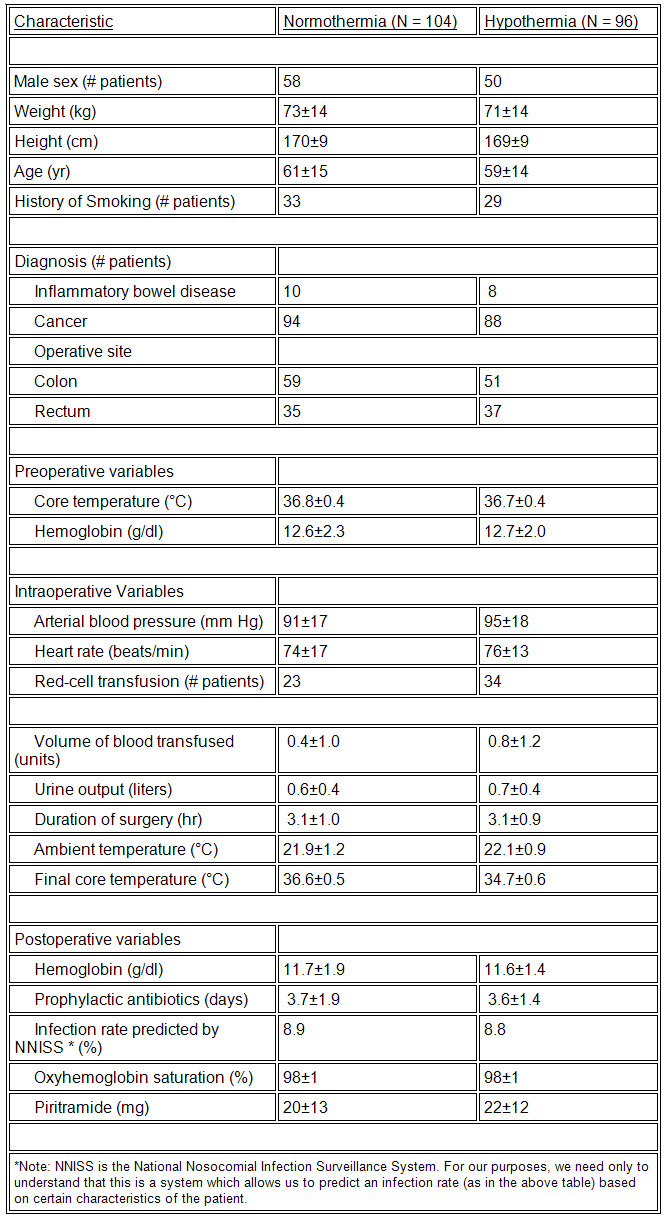

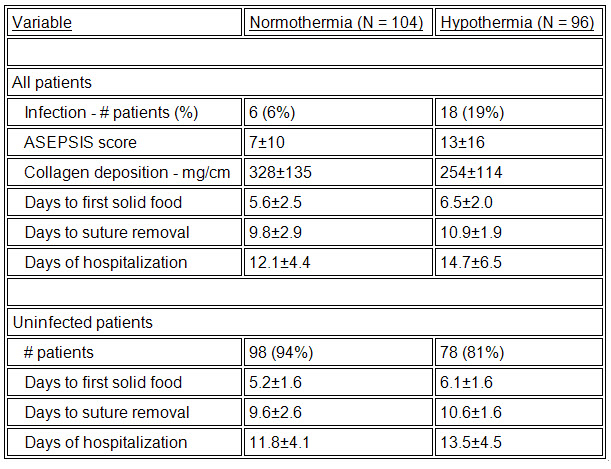

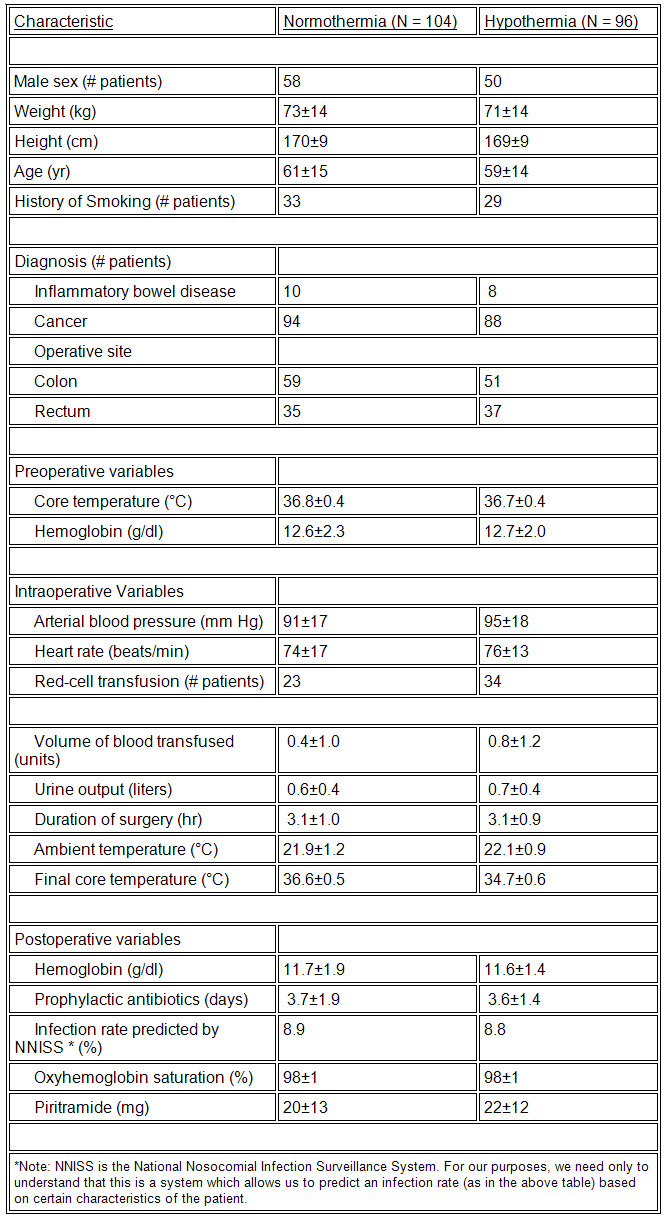

The following are excerpts from tables which were included in the Kurz, Sessler, and Lenhardt (1996) paper. For categorical variables, the tables give the number (and/or percent) of patients; for numerical variables, the tables give the mean ± (plus or minus) one standard deviation.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Patients in the Two Study Groups

Table 2: Postoperative Findings in the Two Study Groups

Table 3: Postoperative Findings in the Study—Patients According to Smoking Status

Johns Hopkins study

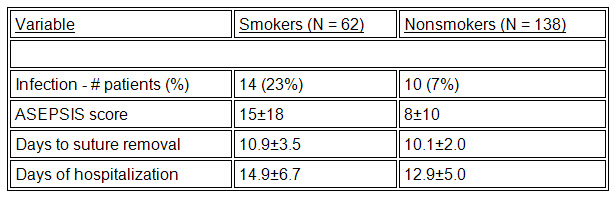

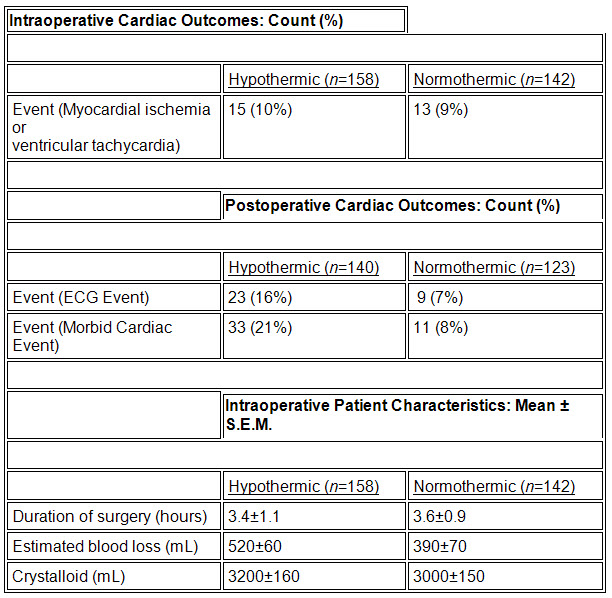

The following are excerpts from tables which appeared in the Frank, et al. (1997) paper. For categorical variables, the tables give counts and percentages; for continuous variables, the tables give mean ± one standard error for the mean.

Questions

a) Was the Austrian study (i) a designed, controlled experiment or (ii) an observational study? Explain.

b) Which of the following might introduce bias into this study? Explain your choice.

(i) One surgeon performs all surgeries on the normothermic group while another performs all surgeries on the hypothermic group.

(ii) For each patient, a fair coin is tossed to determine which surgeon will operate on the patient.

c) Why did the researchers use double-blinding in this study?

a) From the protocol, one knows that the patients were randomly assigned to the normothermia (additional warming) and the hypothermia (routine thermal care) groups. The patients’ care was standardized. Additionally, the experiment was run double-blind. These are all properties of a well-designed, controlled experiment.

b) Randomization is used to eliminate sources of bias from an experiment. The situation with one surgeon performing surgeries on one group and another surgeon performing surgeries on the other group might introduce bias. Possible sources of bias here would be the differing abilities of the surgeons or the surgeons’ beliefs about the effect of temperature on the patient’s outcome.

c)Double-blinding, like randomization, is used to eliminate sources of bias from an experiment. Double-blinding was used throughout the surgical process, from assignment of patients to the treatment and control groups to determination of post-surgical measures. With the patients unaware of which group they were in, psychological biases, such as psychosomatic reactions, should be eliminated. Similarly, with the doctors unaware of which group the patients were in, both operative and post-surgical procedures are based solely on medical determinants, not on any preconceived ideas as to the effectiveness of the treatment.

Review the protocol of the Johns Hopkins study.

a) What variables or (heating) factors are controlled in the Johns Hopkins study?

b) Which factors differ between the treatment and control groups in the Johns Hopkins study?

c) The protocol allows for patients in the control group to be given either one or two warmed cotton blankets, at the nurse's discretion. Explain why the researchers may have chosen to allow such subjectivity in the protocol of the study.

a) The following variables were controlled in the Johns Hopkins study:

b) The use of covering in the intraoperative and postoperative periods is different for the two groups. For the hypothermic group, the patient was covered intraoperatively with one layer of paper surgical drapes, while in the normothermic group, the patient was covered with a forced-air warming blanket. During the postoperative period, the patients in the hypothermic group were covered with one or two warmed cotton blankets, at the discretion of the attending nurse. The normothermic patients were covered postoperatively by the forced-air warming blanket.

c) The control group is intended to mimic and represent routine patient thermal care as much as possible. It is likely that such discretionary use of warmed cotton blankets in the postoperative period is common practice. Secondly, since it had previously been established that hypothermia may lead to increased risk for infections, care must be taken not to subject the patients to extreme cold for the sake of experimentation. Ethical considerations would require that nurses exercise routine medical judgment in order to keep the patient comfortable in the postoperative period.

In the Results section for the Johns Hopkins study, the table of intraoperative patient characteristics gives the mean plus or minus (±) the standard error of the mean for various characteristics.

After reviewing that table, several students from an introductory Statistics class engage in the following debate. Evaluate their comments and decide which, if any, of the arguments are correct.

Student 1: About 95% of the surgeries for patients in the hypothermic group lasted between 1.2 and 5.6 hours. In the normothermic group, about 95% of the surgeries lasted between 1.8 and 5.4 hours.

Student 2: A 95% confidence interval for the mean duration of surgery for hypothermic patients is ![]() = (3.31, 3.49). For normothermic patients the interval is

= (3.31, 3.49). For normothermic patients the interval is ![]() = (3.52, 3.68).

= (3.52, 3.68).

Student 3: The standard error for the mean seems unusually large, since the standard deviation for the individual observations is equal to the standard error of the means multiplied by the square root of n. Thus the mean plus or minus (±) one standard deviation would go far outside the range of possible values for duration of surgery.

Student #3's argument is plausible. Note that the standard deviation for the hypothermic group would be calculated as follows: 1.1*(158)1/2 = 13.83.

Then the mean plus or minus (±) one standard deviation gives the values –10.43 to 17.23 hrs. Since surgery times must be positive many surgeries would have to have lasted more than 24 hrs, which seems unlikely. Perhaps the standard deviation was being reported rather than the standard error of the mean (note the value of 1.1 is very close to the value for the standard deviation in the Austrian study).

Student #1's argument is not correct. This would be a correct interpretation if the mean ± the standard deviation were reported. But if the standard error is given, then these confidence intervals apply to the mean surgery time, not the population of surgery times.

Student #2's answer is not correct. This is also assuming that the mean ± the standard deviation is given. If the standard error is given, the standard deviation has already been divided by the square root of the sample size.

Kurz, Sessler, and Lenhardt (1996) stated that “those who smoked had three times more surgical-wound infections and significantly longer hospitalizations than the nonsmokers.”

a) What do you think the researchers are referring to?

b) The hypothermic group had three times more infections than the normothermic group. Do you think, therefore, that smoking (rather than the treatment) may be the reason for the difference in the number of infections between the normothermic and hypothermic groups?

a) From Table 3 it appears the researchers are referring to the infection rates, which are a little more than three times as high for smokers.

b) From Table 1, one will note that the smoking histories are similar for the two groups. Since both groups are made up of a similar proportion of smokers and nonsmokers due to the randomization, smoking is not a confounding factor. It would be a potential confounding factor if one group or the other had a significantly higher proportion of smokers. [Note: The paper by Kurz, Sessler, and Lenhardt also addressed possible confounding factors other than smoking and discovered that, since the other factors were also similar between the two groups, they were unlikely to have confounded the study.]

Why did the researchers choose to make all of the comparisons listed in Table 1?

Table 1: Characteristics of the Patients in the Two Study Groups

The researchers wished to show that the randomization of patients to treatment and control groups was successful in making the two groups as similar as possible on variables that might otherwise be confounding factors.

Recall that the patients studied by Kurz, Sessler, and Lenhardt (1996) were adults undergoing colon or rectal surgery. Do the results we find in this data carry over to:

One can only make statistical conclusions for the actual group involved in the experiment or the population from which this group is a (random) sample. Using non-statistical arguments, these results can perhaps be generalized (with caution) to groups which are similar to those involved in the experiment. In this case (since the patients are not a random sample from a larger population), it is very risky to extrapolate results to any groups dissimilar to those which were involved in the experiment. While the results might hold for other groups, such as those having other types of surgeries, shorter/longer surgeries, or surgeries on children, there is no statistical evidence that this is the case.

References

Kurz, A., Sessler, D. I., and Lenhardt, R. (1996). “Perioperative Normothermia to Reduce the Incidence of Surgical-Wound Infection and Shorten Hospitalization,” The New England Journal of Medicine, 334 (19), 2109-2115.

Frank, S., Fleisher, L., Breslow, M., Higgins, M., Olson, K., Kelly, S., and Beattie, C., (1997). "Perioperative Maintenance of Normothermia Reduces the Incidence of Morbid Cardiac Events," Journal of the American Medical Association, 277 (14), 1127-1134.

Credits

The Austrian story was prepared by Jackie Miller on 5/18/1997. The Johns Hopkins story was prepared by Brian Millen on 5/28/1997. The final version was completed by Sumithra Ramaswamy and Petra Graham on 12/15/1998. Thanks to Rusch International for supplying a picture of their surgical blanket.